RiskVA

Insect Frauds – Praying Mantises 30 Sep 2015

There are several species of praying mantises in the United States, including a European variety with a scientific name that says it all – Mantis religiosa, that is now common in this country too. In fact, most praying mantises are non-native residents of the U.S. (No, they don’t require Immigration and Naturalization documents.)

Not religious, loving, or docile, praying mantises are masters of fraud. The name mantis derives from Greek, and means “prophet.” So the technical name of this animal translates as “the religious prophet.” But stop right there. These unique insects are neither prophets nor religious. At least I’ve never seen one sitting piously in a pew on Sunday giving its undivided attention to the sermon. And, I know of no prophesies attributed to them.

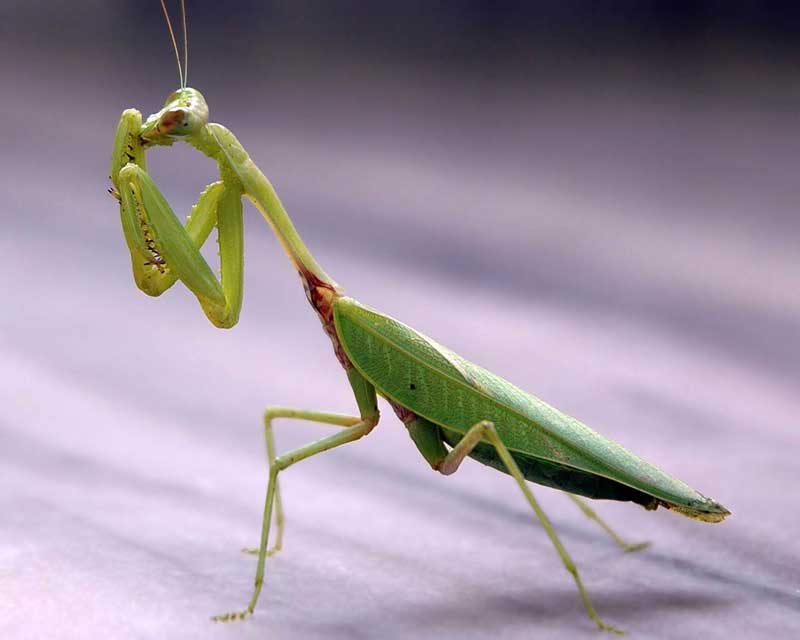

Their common name of praying mantis comes from their habit of standing upright with their modified front legs folded piously in front of them as if in prayer. Although I’ve never had any meaningful conversations with a praying mantis, I have to assume that if they’re praying at all it’s just a supplication that a juicy insect will come by to join them in a meal – or rather, as the main course.

Praying mantises are predatory carnivores, 3-5 inches in length. When a succulent fly, grasshopper, butterfly, moth, bee, or other prey species is careless enough to come close, those folded front legs lash out with lightning speed to grasp their prey. Studded with sharp spines, the target has little or no chance of escape.

Green during spring and early summer, praying mantises turn brown as the season progresses, helping to camouflage them against the changing colors of the vegetation in which they lurk. Much like an owl, mantises can rotate their heads about 180 degrees, allowing their huge eyes to scan the territory and keep dinner in view.

The mantis’ eyes are a marvel in engineering that are extremely sensitive to movement (“all the better to catch you, little fly”), and with great depth of focus. They can see clearly objects up close or far away. No focus problems.

Their two eyes are mounted forward to give them binocular vision – depth perception – much as our eyes work. Each large eye is actually a compound visual organ with thousands of micro “eyes” called ommatidia all working in unison to build the image the mantis sees.

Not all mantises can fly, but those that do can also hear, primarily in the ultrasonic spectrum, higher than the human ear can perceive. That gives them an advantage in avoiding bats, one of their prime enemy attackers. However, they only have one “ear” located on their underside. So they can’t determine the direction of incoming sound. Bats use an ultrasonic attack sonar to zero in on targets. When mantises are in flight and they sense the attack sonar of an incoming bat, they do a power dive and roll toward the ground, perhaps hoping (do mantises hope?) to confuse the attacking bat with ground clutter. It’s an escape maneuver fighter jets also use when their instruments detect targeting radar locked on them.

Breeding takes place in late summer, and the female lays a mass of eggs in a foamy mass an inch so long that turns brownish, and hardens. These egg masses are often found on branches or twigs and the sides of houses. Whether the female actually eats her mate after they couple is questioned by experts, but some apparently do. In spring the eggs hatch and the immature mantises pass through several molts on the way to becoming adults and starting the cycle over. A mantises life span is only a year.

Mantises are very beneficial insects that feed on a variety of pest insects. But they are not very discriminating, also eating beneficial insects such as honey bees. Easy to care for, some people keep praying mantises as pets. However they aren’t really in the same category as a cat that will curl up on your lap and purr, or a faithful companion dog to retrieve your slippers. There’s simply something lacking in their personalities. I’d recommend just leaving them outdoors in our diverse fields and forests.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.