RiskVA

A Snake in the Grass 30 Jul 2008

Sleeping in the shade, Sneaky Snake’s heartbeat was slow and his breathing almost imperceptible. Through much of the night, the cool air temperature forced him into a sluggish, almost comatose state and his life functions were at a low ebb although the creeping cold of the night had so gradually chilled him that he wasn’t really aware of his changed level of activity.

Lacking moveable lids, his eyes were wide open, although he really wasn’t processing any visual information. But a tasty, bite-sized passerby was still nervous about that cold, slit-pupiled gaze and watching fearfully, furtively gave the snake a wide birth, scampering quickly away.

Slowly, the sun shifted and the temperature began to rise. As his body warmed, his heartbeat increased and other life processes gained speed. He began to awaken. With no ears, his body sensed the vibrations of the small scamperer’s footfalls and hunger prompted him to greater alertness. Sniffing or actually tasting the air currents surrounding him with his forked tongue he detected the aroma of the rapidly departing meal, but his dull, almost robotic, reptilian brain determined that pursuit wasn’t likely to result in success.

A more pressing issue was developing. As the sun rose and increased his body temperature, he needed to get into a cooler location before heat stroke claimed his life. With no sweat glands, evaporative cooling was not something he could utilize to maintain a safe body temperature. Actually, he had no biological ability to control his body temperature at all. Keeping himself within a life sustaining temperature range was a matter of seeking warmer, better insulated places when chill crept into his bones and moving into cooler spots when he became too warm.

Using special muscles in his underside, he rhythmically moved his belly scales slightly forward and backward and was thus able to slither straight ahead, and by moving his long slippery body into a series of repeated lateral undulations, he quickly departed the potentially life-threatening blaze of old Sol.

Sneaky didn’t always flee from the sun. On chilly days or arising from slumber, he frequently sought its warmth basking until his body reached optimum operating temperature. But today, it would be hot so his unthinking but accurate response was to get out of the sun.

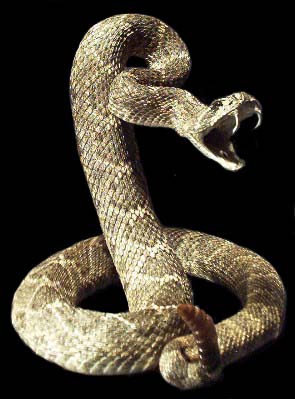

Now fully alert, hunger drove him to hunt for a meal. It had been almost a month since his last snack. Tasting the air again, he sensed another nearby McMousemeal and began to slither closer. The mouse too had been hungry and was inattentively munching a grasshopper when a sudden blow knocked the wind out of him and he felt needle-sharp teeth painfully gripping him as twin shots of venom were injected.

It was a fat mouse and wouldn’t fit into his mouth although all his sharp teeth angled backwards, keeping the struggling mouse from escaping. He had to be careful because a mouse bite could become infected and kill him.

The venom was having its effect and the mouse, his eyes bugging from fear and shortness of breath, struggled for a moment, but to no avail. Within moments, dizziness and darkness welled up and death claimed him.

Now Sneaky relaxed his grip, checked the mouse carefully to assure it was dead and then carefully moved it so that it was face to face with him. His mouth opened again and he began to slowly pull it into his mouth, nose first, the two halves of his lower jaw moving alternately in and out, first the right and then the left, dragging the mouse in. Then an amazing thing occurred. He dislocated his lower jaw from its attachment with his skull, giving the mouse plenty of room to enter his throat. Once past his teeth, rhythmic contractions moved the mouse into the snake’s digestive tract.

Satisfied with his morning hunt, Sneaky crawled away, a long, narrow, scaly, slippery (not slimy) killing machine with a mouse-filled lump in his middle. He wouldn’t have to eat again for another month as he gradually absorbed his meal.

Snakes are amazing, interesting, and without exception, bent on doing their own thing and avoiding encounters with big, flat-footed stompers such as us. So, if you see one, enjoy the experience and be thankful they are in our fields and forests. Otherwise, we could be eyebrow deep in mice and rats. Nice thought, huh?

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.